Firefighting

Firefighting is the act of extinguishing fires. A firefighter fights fires to prevent loss of life, and/or destruction of property and the environment. Firefighting is a highly technical skill that requires professionals who have spent years training in both general firefighting techniques and specialized areas of expertise.

History

These organised teams would use bucket-brigades and syringes to douse a fire.[1]

Ancient Rome

There was no public fire-fighting in the Roman Republic. Instead, private individuals would rely upon their slaves or supporters to take action. This action could involve razing nearby buildings to prevent the spread of fire as well as bucket brigades. The very wealthy Marcus Licinius Crassus was infamous for literal fire sales. He would buy burning buildings at low prices and then have his own several hundred large group of men suppress the fire. If Crassus did not get a price he liked he would let the building burn. Following this, Augustus Caesar introduced a free public service based on Crassus' model.

United Kingdom

Prior to the Great Fire of London in 1666, some parishes in the UK had begun to organise rudimentary firefighting. After much of London was destroyed, the first fire insurance was introduced by a man named Nicholas Barbon. To reduce the cost, Barbon formed his own Fire Brigade, and eventually there were many other such companies. By the start of the 1800s, those with insurance were given a badge or mark to attach to their properties, indicating that they were eligible to utilize the services of the fire brigade. Other buildings with no coverage or insurance with a different company were left to burn [2] unless they were adjacent to an insured building in which case it was often in the insurance company's interest to prevent the fire spreading.

In 1833, companies in London merged to form The London Fire Engine Establishment.

Steam powered appliances were first introduced in the 1850s, allowing a greater quantity of water to be directed onto a fire.

The steam powered appliances were replaced in the early 1900s with the invention of the internal combustion engine.

Firefighters' duties

Firefighters' goals are to save life, property and the environment. A fire can rapidly spread and endanger many lives; however, with modern firefighting techniques, catastrophe is usually, but not always, avoided. To prevent fires from starting, a firefighter's duties include public education and conducting fire inspections.

Because firefighters are often the first responders to people in critical conditions, firefighters provide many other valuable services to the community they serve, such as:

- Emergency medical services, as technicians or as licensed paramedics, staffing ambulances;

- Hazardous materials mitigation (HAZMAT);

- Vehicle Rescue/Extrication;

- Search and rescue;

- Community disaster support.

- Fire Risk Assessments

Additionally, firefighters also provide service in specialized fields, such as:

- Aircraft/airport rescue;

- Wildland fire suppression;

- Shipboard and military fire and rescue;

- Tactical paramedic support ("SWAT medics");

- Tool hoisting;

- High Angle Rope Rescue;

- Swiftwater Rescue.

In the US, firefighters also serve the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as urban search and rescue (USAR) team members.

Hazards caused by fire

The primary risk to people in a fire are not the flames themselves, but rather smoke inhalation, which, contrary to popular belief, is the most common cause of death in a fire. The risks of smoke include:

- suffocation due to the fire consuming or displacing all of the oxygen from the air

- poisonous gases produced by the fire as products of combustion

- aspirating heated smoke that can burn the inside of the lungs and damage their ability to exchange gases during respiration

To combat these potential effects, firefighters carry self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA; an open-circuit positive pressure compressed air system) to prevent smoke inhalation. These are not oxygen tanks; they carry compressed air. SCBA usually hold 30 to 45 minutes of air, depending upon the size of the tank and the rate of consumption during strenuous activities.

Obvious risks are associated with the immense heat. Even without direct contact with the flames (direct flame impingement), conductive heat can create serious burns from a great distance. There are a number of comparably serious heat-related risks: burns from radiated heat, contact with a hot object, hot gases (e.g., air), steam and hot and/or toxic smoke. Firefighters are equipped with personal protective equipment (PPE) that includes fire-resistant clothing (Nomex or polybenzimidazole fiber (PBI)) and helmets that limit the transmission of heat towards the body. No PPE, however, can completely protect the user from the effects of all fire conditions.

Heat can make flammable liquid tanks violently explode, producing what is called a BLEVE (boiling liquid expanding vapor explosion).[3] Some chemical products such as ammonium nitrate fertilizers can also explode. Explosions can cause physical trauma or potentially serious blast or shrapnel injuries.

Heat causes human flesh to burn as fuel, causing potentially severe medical problems. Depending upon the heat of the fire, burns can occur in a fraction of a second.

Additional risks of fire include the following:

- smoke can obscure vision, potentially causing a fall, disorientation, or becoming trapped in the fire;

- structural collapse.

According to a University News Bureau Life Sciences article reported by News Editor Sharita Forest and photographed by L. Brian Stauffer, from the website of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,: "Three hours of fighting a fire stiffens arteries and impairs cardiac function in firefighters, according to a new study by Bo Fernhall, a professor in the department of kinesiology and community health in the College of Applied Health Sciences, and Gavin Horn, director of research at the Illinois Fire Service Institute. The conditions (observed in healthy male firefighters) are "also apparently found in weightlifters and endurance athletes..." (<<http://news.illinois.edu/news/11/0803firefighting_GavinHorn_BoFernhall.html>>)

Reconnaissance and reading the fire

The first step of a firefighting operation is a reconnaissance to search for the origin of the fire (which may not be obvious for an indoor fire, especially when there are no witnesses), and identification of the specific risks and any possible casualties. Any fire occurring outside may not require reconnaissance; on the other hand, a fire in a cellar or an underground car park with only a few centimeters of visibility may require a long reconnaissance to identify the seat of the fire.

The "reading" of the fire is the analysis by the firefighters of the forewarnings of a thermal accident (flashover, backdraft, smoke explosion), which is performed during the reconnaissance and the fire suppression maneuvers. The main signs are:

- Hot zones, which can be detected with a gloved hand, especially by touching a door before opening it;

- Soot on windows, which usually means that combustion is incomplete and thus there is a lack of air;

- Smoke going in and out around a door frame, as if the fire breathes, which usually means a lack of air to support combustion;

- Spraying water on the ceiling with a short pulse of a diffused spray (e.g., cone with an opening angle of 60°) to test the heat of the smoke:

- When the temperature is moderate, the water falls down in drops with a sound of rain,

- When the temperature is high, it vaporizes with a hiss — this can be the sign of an extremely dangerous impending flashover

Ideally, part of reconnaissance is to consult an existing preplan for the building. This provides knowledge of existing structures, firefighter hazards, and can include strategies and tactics.

Science of extinguishment

Fire elements[4]

There are four elements needed to start and sustain a fire and/or flame. These elements are classified in the “fire tetrahedron” and are:

The reducing agent, or fuel, is the substance or material that is being oxidized or burned in the combustion process. The most common fuels contain carbon along with combinations of hydrogen and oxygen. Heat is the energy component of the fire tetrahedron. When heat comes into contact with a fuel, it provides the energy necessary for ignition, causes the continuous production and ignition of fuel vapors or gases so that the combustion reaction can continue, and causes the vaporization of solid and liquid fuels. The self-sustained chemical chain reaction is a complex reaction that requires a fuel, an oxidizer, and heat energy to come together in a very specific way. A chain reaction is a series of reactions that occur in sequence with the results of each individual reaction being added to the rest. This happens in the science of fire, but is self-sustaining in that it continues without interruption. An oxidizing agent is a material or substance that when the proper conditions exist will release gases, including oxygen. This is crucial to the sustainment of a flame or fire.

A fire can be extinguished by taking away any of the four components of the tetrahedron.[4] One method to extinguish a fire is to use water. The first way that water extinguishes a fire is by cooling, which removes heat from the fire. This is possible through water’s ability to absorb massive amounts of heat by converting water to water vapor. Without heat, the fuel cannot keep the oxidizer from reducing the fuel to sustain the fire. The second way water extinguishes a fire is by smothering the fire. When water is heated to its boiling point, it converts to water vapor. When this conversion takes place, it dilutes the oxygen in the air with water vapor, thus removing one of the elements that the fire requires to burn. This can also be done with foam.

Another way to extinguish a fire is fuel removal. This can be accomplished by stopping the flow of liquid or gaseous fuel or by removing solid fuel in the path of a fire. Another way to accomplish this is to allow the fire to burn until all the fuel is consumed, at which point the fire will self-extinguish.

One final extinguishing method is chemical flame inhibition. This can be accomplished through dry chemical and halogenated agents. These agents interrupt the chemical chain reaction and stop flaming. This method is effective on gas and liquid fuels because they must flame to burn.

Use of water

Often, the main way to extinguish a fire is to spray with water. The water has two roles:

- in contact with the fire, it vaporizes, and this vapour displaces the oxygen (the volume of water vapour is 1,700 times greater than liquid water, at 1,000°F (540°C) this expansion is over 4,000 times); leaving the fire with insufficient combustive agent to continue, and it dies out.[3]

- the vaporization of water absorbs the heat; it cools the smoke, air, walls, objects in the room, etc., that could act as further fuel, and thus prevents one of the means that fires grow, which is by "jumping" to nearby heat/fuel sources to start new fires, which then combine.

The extinguishment is thus a combination of "asphyxia" and cooling. The flame itself is suppressed by asphyxia, but the cooling is the most important element to master a fire in a closed area.

Water may be accessed from a pressurized fire hydrant, pumped from water sources such as lakes or rivers, delivered by tanker truck, or dropped from aircraft tankers in fighting forest fires.

Open air fire

For fires in the open, the seat of the fire is sprayed with a straight spray: the cooling effect immediately follows the "asphyxia" by vapor, and reduces the amount of water required. A straight spray is used so the water arrives massively to the seat without being vaporized before. A strong spray may also have a mechanical effect: it can disperse the combustible product and thus prevent the fire from starting again.

The fire is always fed with air, but the risk to people is limited as they can move away, except in the case of wildfires or bushfires where they risk being easily surrounded by the flames.

Spray is aimed at a surface, or object: for this reason, the strategy is sometimes called two-dimensional attack or 2D attack.

It might be necessary to protect specific items (house, gas tank, etc.) against infrared radiation, and thus to use a diffused spray between the fire and the object.

Breathing apparatus is often required as there is still the risk of inhaling smoke or poisonous gases.

Closed volume fire

Until the 1970s, fires were usually attacked while they declined, so the same strategy that was used for open air fires was effective. In recent times, fires are now attacked in their development phase as:

- firefighters arrive sooner;

- thermal insulation of houses confines the heat;

- modern materials, especially the polymers, produce a lot more heat than traditional materials (wood, plaster, stone, bricks, etc.).

Additionally, in these conditions, there is a greater risk of backdraft and of flashover.

Spraying of the seat of the fire directly can have unfortunate and dramatic consequences: the water pushes air in front of it, so the fire is supplied with extra oxygen before the water reaches it. This activation of the fire, and the mixing of the gases produced by the water flow, can create a flashover.

The most important issue is not the flames, but control of the fire, i.e., the cooling of the smoke that can spread and start distant fires, and that endangers the lives of people, including firefighters. The volume must be cooled before the seat is treated. This strategy originally of Swedish (Mats Rosander & Krister Giselsson) origin, was further adapted by London Fire Officer Paul Grimwood following a decade of operational use in the busy West End of London between 1984-94 (www.firetactics.com) and termed three-dimensional attack, or 3D attack.

Use of a diffused spray was first proposed by Chief Lloyd Layman of the Parkersburg Fire Department, at the Fire Department Instructors Conference (FDIC) in 1950 held in Memphis.

Using Grimwood's modified 3D attack strategy, the ceiling is first sprayed with short pulses of a diffused spray:

- it cools the smoke, thus the smoke is less likely to start a fire when it moves away;

- the pressure of the gas drops when it cools (law of ideal gases), thus it also reduces the mobility of the smoke and avoids a "backfire" of water vapour;

- it creates an inert "water vapour sky", which prevents roll-over (rolls of flames on the ceiling created by the burning of hot gases).

Only short pulses of water must be sprayed, otherwise the spraying modifies the equilibrium, and the gases mix instead of remaining stratified: the hot gases (initially at the ceiling) move around the room and the temperature rises at the ground, which is dangerous for firefighters. An alternative is to cool all the atmosphere by spraying the whole atmosphere as if drawing letters in the air ("penciling").

The modern methods for an urban fire dictate the use of a massive initial water flow, e.g. 500 L/min for each fire hose. The aim is to absorb as much heat as possible at the beginning to stop the expansion of the fire, and to reduce the smoke. When the flow is too small, the cooling is not sufficient, and the steam that is produced can burn firefighters (the drop of pressure is too small and the vapor is pushed back). Although it may seem paradoxical, the use of a strong flow with an efficient fire hose and an efficient strategy (diffused sprayed, small droplets) requires a smaller amount of water: once the temperature is lowered, only a limited amount of water is necessary to suppress the fire seat with a straight spray. For a living room of 50m² (60 square yards), the required amount of water is estimated as 60 L (15 gal).

French firefighters used an alternative method in the 1970s: they sprayed water on the hot walls to create a water vapour atmosphere and asphyxiate the fire. This method is no longer used because it was risky; the pressure created pushed the hot gases and vapour towards the firefighters, causing severe burns, and pushed the hot gases into other rooms where they could start a new fire.

Asphyxiating a fire

In some cases, the use of water is undesirable:

- some chemical products react with water and produce poisonous gases, or even burn in contact with water (e.g., sodium);

- some products float on water, e.g., hydrocarbon (gasoline, oil, alcohol, etc.); a burning layer can then spread and extend;

- in case of a pressurised fuel tank, it is necessary to avoid heat shocks that may damage the tank: the resulting decompression may produce a BLEVE;

- electrical fires where water would act as a conductor.

It is then necessary to asphyxiate the fire. This can be done in different ways:

- some chemical products react with the fuel and stop the combustion;

- a layer of water-based fire retardant foam is projected on the product by the fire hose, to keep the oxygen in air separated from the fuel;

- carbon dioxide.

Tactical ventilation or isolation of the fire

One of the main risks of a fire is the smoke: it carries heat and poisonous gases, and obscures vision. In the case of a fire in a closed location (building), two different strategies may be used: isolation of the fire, or ventilation.

Paul Grimwood introduced the concept of tactical ventilation in the 1980s to encourage a better thought-out approach to this aspect of firefighting. Following work with Warrington Fire Research Consultants (FRDG 6/94) his terminology and concepts were adopted officially by the UK fire services, and are now referred to throughout revised Home Office training manuals (1996–97).

Grimwood's original definition of his 1991 unified strategy stated that, "tactical ventilation is either the venting, or containment (isolation) actions by on-scene firefighters, used to take control from the outset of a fire's burning regime, in an effort to gain tactical advantage during interior structural firefighting operations."

Ventilation affects life safety, fire extinguishment, and property conservation. First, it pulls fire away from trapped occupants when properly used. It may also "limit fire spread by channeling fire toward nearby openings and allows fire fighters to safely attack the fire" as well as limit smoke, heat, and water damage.[5]

Positive pressure ventilation (PPV) consists of using a fan to create excess pressure in a part of the building; this pressure will push the smoke and the heat out of the building, and thus secure the rescue and fire fighting operations. It is necessary to have an exit for the smoke, to know the building very well to predict where the smoke will go, and to ensure that the doors remain open by wedging or propping them. The main risk of this method is that it may accelerate the fire, or even create a flashover, e.g., if the smoke and the heat accumulate in a dead end.

Hydraulic ventilation is the process of directing a stream from the inside of a structure out the window using a fog pattern.[3] This effectively will pull smoke out of room. Smoke ejectors may also be used for this purpose.

Categorising fires

In the US, fires are sometimes categorised as "one alarm", "all hands", "two alarm", "three alarm" (or higher) fires. There is no standard definition for what this means quantifiably, though it always refers to the level response by the local authorities. In some cities, the numeric rating refers to the number of fire stations that have been summoned to the fire. In others, the number counts the number of "dispatches" for additional personnel and equipment.[6][7]

Alarms are generally used to define the tiers of the response by what resources are used.

Example:

Structure fire response draws the following equipment:

- 3 Engine/Pumper Companies

- 1 Truck/ladder/aerial Company

This is referred to as an Initial Alarm or Box Alarm.

Working fire request (for the same incident)

- Air/Light Units

- Other specialized rescue units

- Chief Officers/Fireground Commanders (if not on original dispatch)

Note: This is the balance of a First Alarm fire.

Second and subsequent Alarms:

- 2 Engine Companies

- 1 Truck Company

The reason behind the "Alarm" is so the Incident Commander doesn't have to request each apparatus with the dispatcher. He can say "Give me a second alarm here", instead of saying "Give me a truck company and two engine companies" along with requesting where they come from.

Keep in mind that categorization of fires varies between each fire department. A single alarm for one department may be a second alarm for another. Response always depends on the size of the fire and the department.

Appendix: calculating the amount of water required to suppress a fire in a closed volume

In the case of a closed volume, it is easy to compute the amount of water needed. The oxygen (O2) in air (21%) is necessary for combustion. Whatever the amount of fuel available (wood, paper, cloth), combustion will stop when the air becomes "thin", i.e. when it contains less than 15% oxygen. If additional air cannot enter, we can calculate:

- The amount of water required to make the atmosphere inert, i.e., to prevent the pyrolysis gases to burn—this is the "volume computation"

- The amount of water required to cool the smoke, the atmosphere—this is the "thermal computation"

These computations are only valid when considering a diffused spray that penetrates the entire volume. This is not possible in the case of a high ceiling: the spray is short and does not reach the upper layers of air. Consequently the computations are not valid for large volumes such as barns or warehouses: a warehouse of 1,000 m² (1,200 square yards) and 10 m high (33 ft) represents 10,000 m3. In practice, such large volumes are unlikely to be airtight anyway.

Volume computation

Fire needs air; if water vapour pushes all the air away, the fuel can no longer burn. But the replacement of all the air by water vapour is harmful for firefighters and other people still in the building: the water vapour can carry much more heat than air at the same temperature (one can be burnt by water vapour at 100 °C (212 °F) above a boiling saucepan, whereas it is possible to put an arm in an oven—without touching the metal!—at 270 °C (520 °F) without damage). This amount of water is thus an upper limit that should not be reached.

The optimal, and minimum, amount of water to use is the amount required to dilute the air to 15% oxygen: below this concentration, the fire cannot burn.

The amount used should be between the optimal value and the upper limit. Any additional water would just run on the floor and cause water damage without contributing to fire suppression.

Let:

- Vr be the volume of the room,

- Vv be the volume of vapour required,

- Vw be the volume of liquid water to create the Vv volume of vapour,

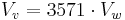

then for an air at 500 °C (773 K, 932 °F, best case concerning the volume, probable case at the beginning of the operation), we have[1]

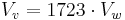

and for a temperature of 100 °C (373 K, 212 °F, worst case concerning the volume, probable case when the fire is suppressed and the temperature is lowered):[2]

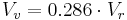

For the maximum volume, we have:

considering a temperature of 100 °C. To compute the optimal volume (dilution of oxygen from 21 to 15%), we have[3]

for a temperature of 500 °C. The table below show some results, for rooms with a height of 2.70 m (8 ft 10 in).

| Amount of water required to suppress the fire volume computation |

|||

| Area of the room | Volume of the room Vr | Amount of liquid water Vw | |

|---|---|---|---|

| maximum | optimal | ||

| 25 m² (30 yd²) | 67.5 m³ | 39 L (9.4 gal) | 5.4 L (1.3 gal) |

| 50 m² (60 yd²) | 135 m³ | 78 L (19 gal) | 11 L (2.7 gal) |

| 70 m² (84 yd²) | 189 m³ | 110 L (26 gal) | 15 L (3.6 gal) |

Note that the formulas give the results in cubic meters, which are multiplied by 1,000 to convert to liters.

Of course, a room is never really closed, gases can go in (fresh air) and out (hot gases and water vapour) so the computations will not be exact.

Notes

- ^ indeed, the mass of one mole of water is 18 g, a liter (0.001 m³) represents one kilogram i.e. 55.6 moles, and at 500 °C (773 K), 55.6 moles of an ideal gas at atmospheric pressure represents a volume of 3.57 m³.

- ^ same as above with a temperature of 100 °C (373 K), one liter of liquid water produces 1.723 m³ of vapour

- ^ we consider that only Vr - Vv of the original room atmosphere remains (Vv has been replaced by water vapour). This atmosphere contains less than 21% of oxygen (some was used by the fire), so the remaining amount of oxygen represents less than 0,21·(Vr-Vv). The concentration of oxygen is thus less than 0,21·(Vr-Vv)/Vr, and we want this fraction to be 0.15 (15%).

See also

- Glossary of firefighting – list of firefighting terms and acronyms, with descriptions

- Glossary of firefighting equipment – expansion of Glossary of firefighting

- Glossary of wildfire terms – expansion of Glossary of firefighting

- Index of firefighting articles – alphabetical list of firefighting articles

- Outline of firefighting – structured list of firefighting topics, organized by subject area

References

- ^ http://www.fireservice.co.uk/history

- ^ http://www.fireservice.co.uk/history

- ^ a b c Thomson Delmar Learning. The Firefighter's Handbook: Essentials of Fire Fighting and Emergency Response. Second Edition. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Publishers, 2004.

- ^ a b Hall, Richard. Essentials of Fire Fighting. Fourth Edition. Stillwater, OK: Fire Protection Publications, 1998:

- ^ Bernard Klaene. Structural Firefighting: Strategies and Tactics. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2007. ISBN 0763751685, 9780763751685

- ^ NBC4.com

- ^ Thevillager.com